What Law Was Passed to Prevent Lusitania Type Incident Again

"The Germans take been trying to spoil our merchandise for some time, but never until today have they manifested such an actively friendly desire to put us out of business. I anticipate that from this time on every German method that can be devised volition exist used to proceed people from traveling on our ships."

–Charles Sumner, Cunard representative, May 1, 1915

As May arrived in 1915, soldiers were mired in trenches across France and Belgium, poison gas had been deployed confronting troops of both sides, and Germany had begun rationing nutrient owing to a British naval blockade. The Imperial Navy stopped all ships suspected of carrying cargo to the Primal Powers and confiscated the materiel. In retaliation, Germany declared the waters surrounding the British Isles a war zone and sent U-boats to patrol the area. In this tense atmosphere, the great Cunard liner, RMS Lusitania, began her 202nd transatlantic crossing carrying one,265 passengers, 694 crew, $735,579 in cargo (1915 value), and three High german speaking stowaways.

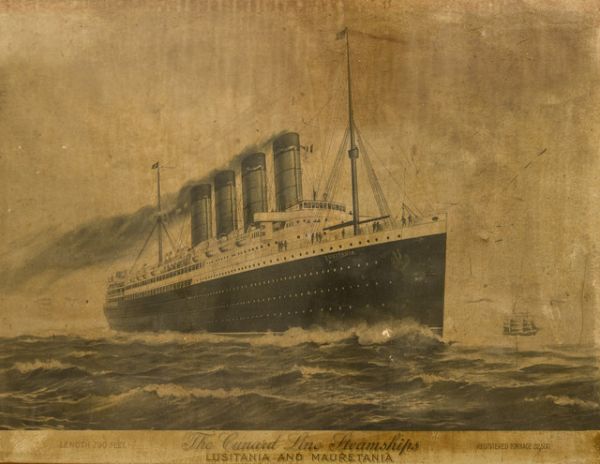

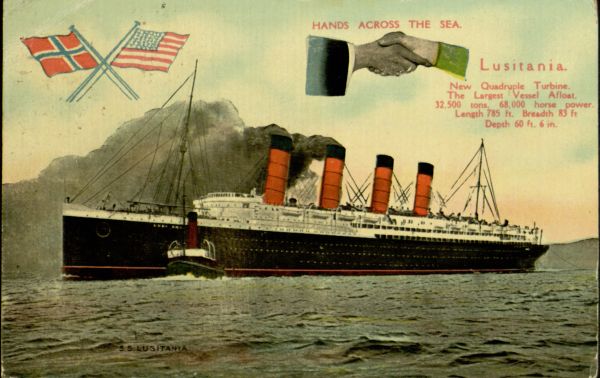

The Lusitania and her sis send the Mauretania were built to dominate the luxury transatlantic passenger trade. At the end of the 19 th century, the iconic Cunard Steamship Line was losing business to an American conglomerate , headlined by the White Star Line and owned by financier JP Morgan, and the Germans . To maintain its hegemony, Cunard needed to build newer, faster, and more luxurious transport southward, but lacked the funds . Emphasizing the British Empire 's competitive disadvantage, Cunard appealed to the government for a loan. Parliament responded with £ 2.six million to construct the two largest and fastest ships on the seas. Until the loan was repaid, the Admiralty own ed a percent of the ships , and Cunard would turn them over to the Navy for use in the event of hostilities. Cunard also had to remain in British hands . No foreign investor could ever ain a share of the not bad steamship line.

Lusitania Elevation and Deck Plans

The ship design committee had a tall order to fill. Cunard wanted a luxury hotel for two , 300 guests while t he Admiralty required an armored cruiser. They stipulated that the ship could exist no longer than 760 feet at the waterline and its coal bunkers should run along the sides of the hull to provide an actress measure out of protection, information technology was thought, from torpedoes. For 8 years later her 1907 launch , the Lusitania was one of ii fastest, well-nigh luxurious (excepting the brief service of the Titanic ) ships on the sea.  The kickoff ocean liner propelled past modern steam turbine engines , he r fastest average speed clocked in at 25.65 knots. This earned the ship four transatlantic records, the coveted Blue Riband . When Europe exploded in August of 1914, the Admiralty immed iately commandeered most British passenger ships to act every bit troop transports. However, it soon found that the largest liners were difficult to maneuver in port and a voracious ambition for coal start the benefit of speed . The "Neat Greyhound " was returned to civilian service, but remained on the official list of British armored cruisers

The kickoff ocean liner propelled past modern steam turbine engines , he r fastest average speed clocked in at 25.65 knots. This earned the ship four transatlantic records, the coveted Blue Riband . When Europe exploded in August of 1914, the Admiralty immed iately commandeered most British passenger ships to act every bit troop transports. However, it soon found that the largest liners were difficult to maneuver in port and a voracious ambition for coal start the benefit of speed . The "Neat Greyhound " was returned to civilian service, but remained on the official list of British armored cruisers

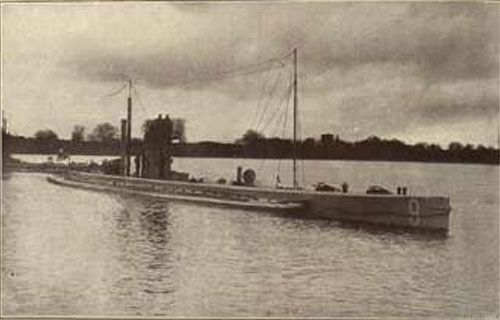

Although submarines had been in service since the American Ceremonious War, the y were relatively untested . No one knew exactly what role the submarine would play in a naval war. Most were coa stal vessels, unable to operate far from port . T he Royal Navy had only acquired reliable long-range submarines in 1907, and Germany in 1913 . These newer ships could range equally far as five , 000 miles and run at surface speeds of 10 to fifteen knots. Underwate r they ran on bombardment ability. On the surface, diesel engines provided propulsion and recharged the batteries. Time submerged had to be balanced with time on the surface in order to keep the batteries charged and ready for an set on, or an escape.

In 1914 , Navies operated under "Cruiser rules , " international guidelines written for encountering enemy merchant ships in a state of war zone. These rules stipulated that offenders w ould exist given a shot across the bow and made to finish. After , a "prize coiffure" would be put aboard to take possession of the ship or, o nce passengers and crew were taken off , the ship w ould be sunk. North eutral ships could also be seized or sunk i f found carrying troops or supplies for the enemy . While these rules worked for large ships, they were both impractical and unsafe for submarines. Not only could subs not take on a ship's crew or cargo before sinking information technology, they were extremely vulnerable to ramming while on the surface. In fact, in October of 1914 , Winston Churchill, Outset Lord of the Admiralty , issue d orders directing all ships to ram any U-gunkhole they encountered . This was in direct contravention of cruiser rules, which stipulated peaceful compliance, and made U-gunkhole captains hesitant to challenge whatsoever ship before attacking.

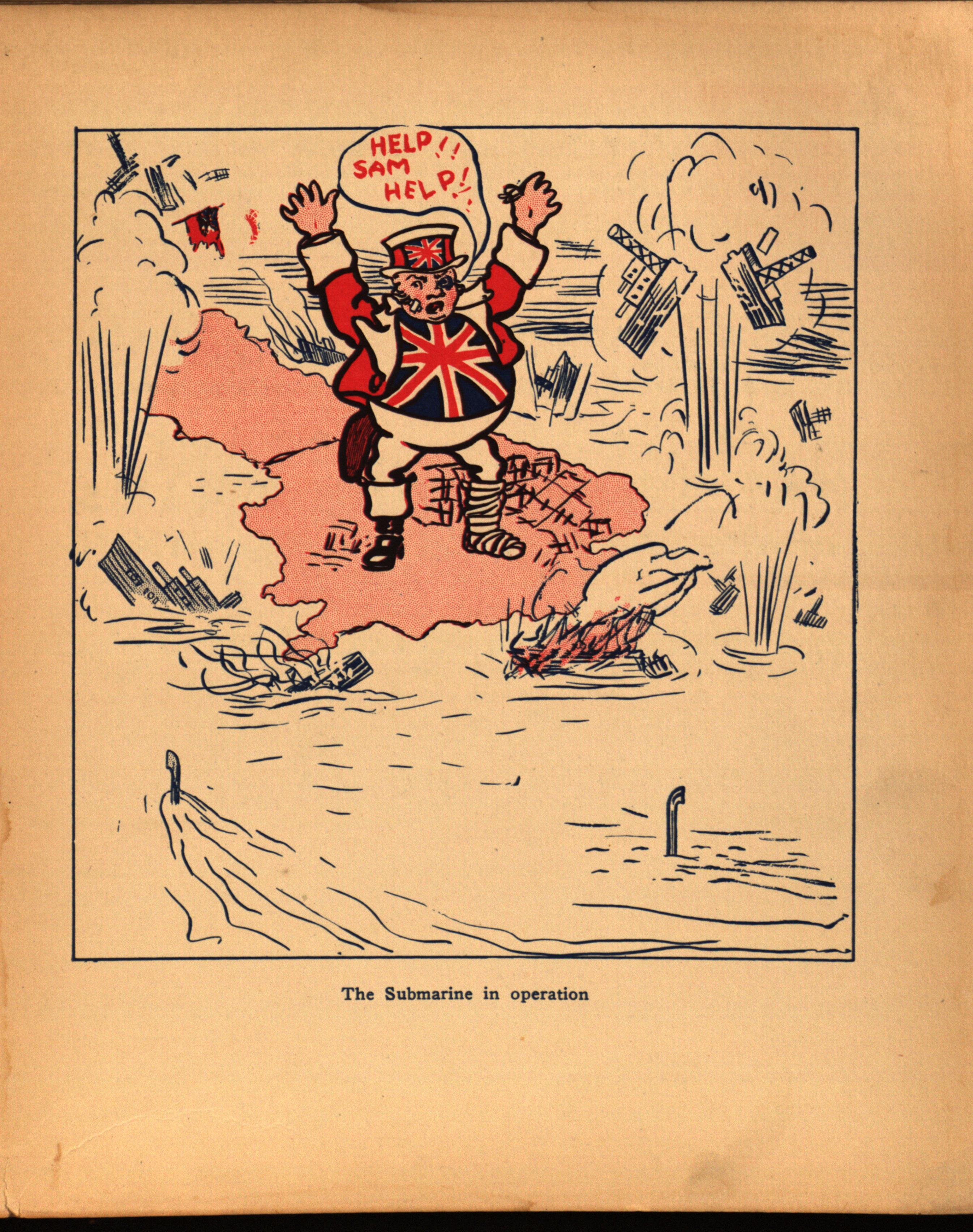

At the kickoff of the Bully War, assertive that victory would come on the seas, not on land , the British Royal Navy initiated a blockade of the Fundamental Powers . A ll ships suspected of carrying contraba nd cargo wer e stopped and the material confisca ted . At outset they were merely looking for munitions and military goods, merely Britain quickly added more items , such as metals, cotton, and most importantly food , to the official contraband listing. On February 4, 1915, f rustrated past the blockade, the Germ ans declared the waters effectually the British Isles a state of war zone and sent U-boats to enforce it .  Admiral Alexander Duff of the British Royal Navy noted in his diary that, "With submarines alone she [Deutschland] cannot promise to inflict any serious damage on our merchant shipping." (Richard Hough, The Groovy War at Bounding main ) Yet, from the February 4 th to May i , German U-boats sank 68 ships, Entent e and neutral. R oughly 200 lives were lost.

Admiral Alexander Duff of the British Royal Navy noted in his diary that, "With submarines alone she [Deutschland] cannot promise to inflict any serious damage on our merchant shipping." (Richard Hough, The Groovy War at Bounding main ) Yet, from the February 4 th to May i , German U-boats sank 68 ships, Entent e and neutral. R oughly 200 lives were lost.

On April xxx, 1915, a German unterseeboot , the U-xx, commanded by Kapitänleutnant Walter Schwe iger , set sheet up the North Sea destined for Liverpool. Her mission was to patrol outside the Mersey bar, a sandbar that, in depression tide, blocked access to the Mersey River and thus, the port of Liverpool. Ships wishing to canvas up the river had to expect for the tide to turn. Germany sent out the U-20 and ii other U-boats in response to rumors of British troop movements from western ports. The Admiralty kept tabs on the parting subs past listening in on their wireless traffic. They had been intercepting and deciphering German messages since the previous F all when c ode books for the Imperial Navy cruel into Russian hands and , ultimately were shared with the British . Winston Churchill, Commencement Lord of the Admiralty, established a group known by their location, Room 40, to interpret High german messages. As U-20'southward wireless operator reported in until the ship left radio range , Room 40 followed the U-20 out of Emden, up the Heligoland Bight, and into Due north Sea .

The U-20'due south journey was slowed past heavy fog . In the days before sonar , submarines relied on sight and sound to forbid collisions. U-boats were especially vulnerable as they rode depression in the water and were not about to signal their position with a foghorn or bell. Foggy days and almost nights, even clear ones, were spent deep underwater , out of impairment's way. The electric engines she used when submerged were dramatically slower than the diesel , so the send did non make headway as planned. Forced to spend extra time in the Atlantic south of Ireland, Schwieger stalked passing ships, sinking the Earl of Lathom on May 5 thursday , and the steamships Candidate and Centurion May 6 thursday . She sighted the White Star liner Arabic, just was non in a good position to attack.

On May 1, 1915, the American morning papers carried a alert from the German embassy, reminding travelers, "that a state of war exists between Germany … and Slap-up Britain," and that those "sailing in the war zone … do so at their ain risk." While not specifically directed at the Lusitania, the notice was placed alongside an advert for Cunard's Europe via Liverpool service. Reporters flocked to the Cunard terminal at New York'south Pier 54, where the Lusitania was preparing to depart. That evening, papers carried stories of threatening telegrams and shady characters with messages of doom weaving amidst gathering passengers. Cunard spokesman Charles P. Sumner reassured the press that while, "The fact is that the Lusitania is the safest boat on the ocean. She is too fast for whatsoever submarine." (New York Evening World, May one, 1915) Merely two canceled bookings were attributed to the warning.

On May 1, 1915, the American morning papers carried a alert from the German embassy, reminding travelers, "that a state of war exists between Germany … and Slap-up Britain," and that those "sailing in the war zone … do so at their ain risk." While not specifically directed at the Lusitania, the notice was placed alongside an advert for Cunard's Europe via Liverpool service. Reporters flocked to the Cunard terminal at New York'south Pier 54, where the Lusitania was preparing to depart. That evening, papers carried stories of threatening telegrams and shady characters with messages of doom weaving amidst gathering passengers. Cunard spokesman Charles P. Sumner reassured the press that while, "The fact is that the Lusitania is the safest boat on the ocean. She is too fast for whatsoever submarine." (New York Evening World, May one, 1915) Merely two canceled bookings were attributed to the warning.

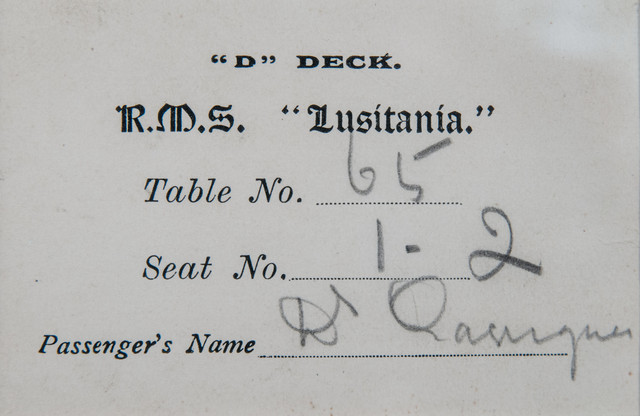

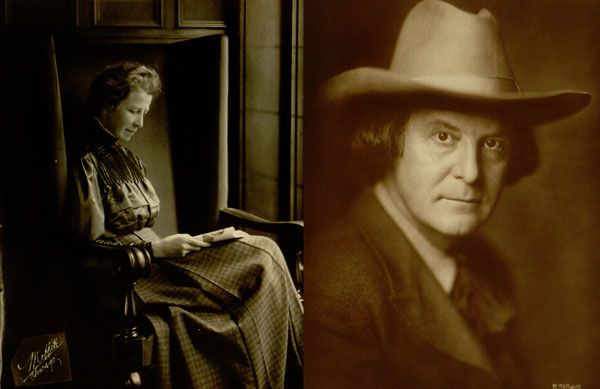

That afternoon, the Lusitania , captained by William Thomas Turner, left on what would be her final voyage. A board were business travelers, families returning to England because of the war , and an unusually big number of children. It was the largest grouping of passengers since the outbreak of war . Notable names found aboard included Vanderbilt heir Alfred, author and Roycroft colony founder Elbert Hubbard, feminist writer Alice Hubbard, Broadway producer Charles Frohman, Antiquarian bookseller Charles Lauriat, extra Rita Jolivet , and the Hodges family unit, of Philadelphia , accompanying father William on business to France. Other passengers included seaman Leslie Morton and his brother John who jumped ship in New York in order to enlist in the state of war effort. They booked passage abode on the Lusitania simply to be recruited to work on the brusque- staffed steamer. Carmine Cross volunteers Elizabeth Seccombe and her brother Percy were on their way to help with the war effort, and Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Agnew, were returning to Ireland , after four years in Pennsylvania , to run the family unit farm later the death of Thomas' male parent.

Alice Moore Hubbard and Elbert Hubbard

D u east in Liverpool May six, the Lusitania was behind schedule from the start . A last minute transfer of passengers from the liner Cameronia , commandeered by the Admiralty , delayed her divergence. Besides, u nbeknownst to the passengers, the Lusitania was non operating at full capacity. D emand for transatlantic servi c due east had declined in the last ix months and despite the mothballing of the Mauretania and other line r due south, n 1 of the Lusitania 'south passages were fully booked. Cunard, to save money on coal , close down six of her 25 boilers. This reduced her superlative boilerplate running speed from 25 knots to 21 knots , still faster than nigh civilian ships, just no longer a record setting footstep. Passengers betting in the daily pool on the distance traveled , non noting the lack of smoke from one of her four funnels, were puzzled by her lack of progress. "The speed of the gunkhole was not what I expected it would be, for after the first full run of 24 hours, in which we covered 501 miles, the run dropped each day to well below the 500 mark, and the final 24 hours upward to Fri noon (May 7) we made only 462 miles." (Charles Lauriat, The Lusitania's Last Voyage )

1909 Postcard sent from aboard the Lusitania

Fog near Ireland as well caused the ship to slow. Every bit the clouds lifted earlier noon on May seven th , the lighthouse atop Ol d Caput at Kinsale was revealed and Captain Turner faced a dilemma. The Lusitania could increase her stride every bit the danger of standoff receded with the fog, only even traveling at top speed she would reach the Mersey Bar after loftier tide that evening and exist require d to wait until morning to sail into port. Turner, knowing that information technology would exist unsafe to bide time in that area, elected to travel at a slower pace, a consistent 18 knots, and fourth dimension his arrival to coincide with high tide . Turner ordered his Beginning Officer, John Preston Piper, to take a four-point bearing, that is , to measure the ship's altitude from a shore landmark in relation to all 4 compass points. This would allow Turner to confirm his estimate of the Lusitania 'south location since the fog had obscured the shoreline all morning, and to corroborate his calculated inflow fourth dimension off the Mersey Bar.

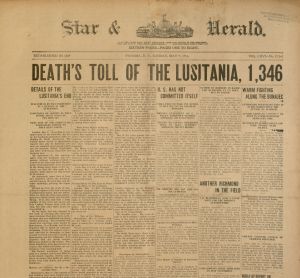

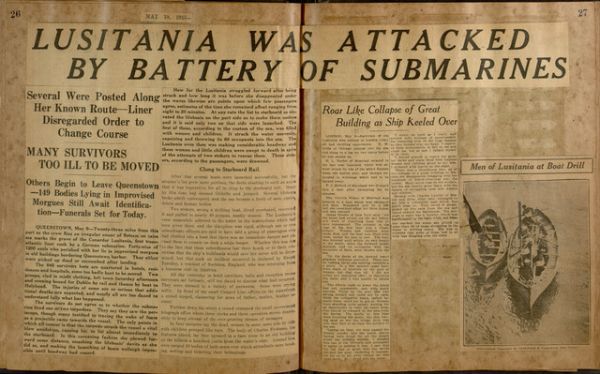

The u-boat and the liner met approximately twelve miles off the Irish coast on the afternoon of May seven. Equally the U-20 was turning for home, the fog lifted and Schweiger caught sight of the ship though his periscope. Although t he Lusitania was steaming at 18 knots, normally fast enough to outrun a U-boat, she made an unfortunate turn to brainstorm the four-indicate begetting that put her in an platonic position for Schweiger . One torpedo, and an unexplained subsequent explosion, sent the gre at ship to the bottom in a mere 18 minutes. ane,198 Argentinean, Belgian, Brazilian, Danish, Dutch, Greek, Italian, Mexican, Norwegian, Russian, Spanish, Swedish, Swiss, British , American, French, Persian, and German language lives were lost.

The finger pointing began immediately. Despite knowing that in that location was an active submarine in the area, the Admiralty did non divert the Lusitania from its course and ship information technology on the safer Northern route because to practice then would allow on that they had prior cognition of the U-20s mission . Drastic to hide the fact that they had been decoding and following German language radio traffic for months, the Admiralty did their best to plow attention from British failures to warn the ship of the U-twenty'south presence. To avoid arraign for putting the Lusitania in harm ' due south way, the Admiralty and Cunard Company focused, at beginning, on Captain Turner. Cunard claimed that he did not tak e adequate precautions against a submarine set on. In fact, Turner did outcome orders to seal all portholes, to swing the lifeboats out over the water in readiness position, and to observe coma atmospheric condition, but he did not steer the ship in a defensive zigzag pattern or steam at pinnacle speed. Cunard had not ordered the latter measures since, as part of the loan understanding, they were not in control of the ship 's movements within the state of war zone. T he Admiralty claimed they had issue d orders for all ships to zigzag , but information technology was later shown that these orders postdated the attack. For his part, Turner expected the Admiralty to provide an armed escort within the war zone, and had been promising ane to the passengers throughout the voyage. Would t he escort have prevented the set on? At the subsequent hearing , Turner stated , " [I]t is 1 of those things one never knows. The submarine would probably accept torpedoed both of usa ." (Eric Larson, Dead Wake )

Misinformation and Speculation were Rife

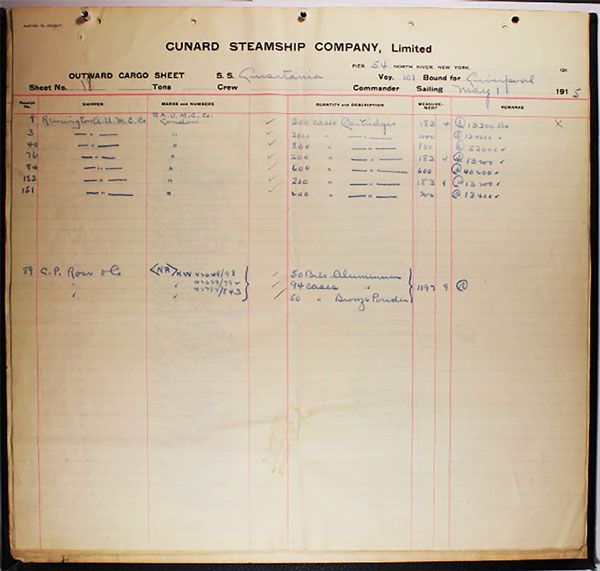

The British and American governments also needed to deflect speculation about the blazon of cargo carried by the passenger liner. The manifest listed 1 , 271 cases of shrapnel shells and 4,000 cases of small arms ammunition, but stories circulated citing bales of gun cotton wool, chemicals, and large munitions on board. These rumors strengthened the German position that the Lusitania was a legitimate target. The cargo was also cited by many as the cause of the second, more violent explosion on board. The Admiralty and the U.s.a. government denied these allegations, and stubbornly stuck to the story of a 2nd torpedo fired by the U-20. (The explosion has too been attributed to a ruptured boiler and/or the presence of coal grit shaken loose from the sides of the nearly empty coal bunkers) T he Admiralty quickly convened an official inquiry into "the loss of the steamship Lusitania ." Led by Lord Mersey, the panel convened June 15, 1915 and interviewed surviving passengers, crew members, rescuers, Admiralty officials , and Captain Turner. Despite testimony to the contrary, t he official finding of the British panel found that two torpedoes had struck the Lusitania . They laid arraign directly at the anxiety of the Germans, whose "act was done not merely with the intention of sinking the ship, but as well with the intention of destroying the lives of the people on lath." ( Harrisburg Telegraph , July 17, 1915)

Page of the cargo manifest listing ammunition aboard the Lusitania

The British press condemned the "Hun'south most ghastly crime" ( Daily Chronicle [Liverpool], May 8, 1915) and there was rioting in England and Canada. German newspapers were jubilant, while the Kaiser'south government held its jiff waiting to see what the Usa would do. The war hawks, exemplifi ed by former president Theo dore Roosevelt, were prepare to jump in to the fray. Ii days after the sinking, Roosevelt warned, in a pamphlet entitled Murder on the Loftier Seas , "Unless we act with immediate decision and vigor we shall accept failed in the duty demanded past humanity at big, and demanded even more clearly past the self-respect of the American Republic." Colonel Edward Firm, advisor to the President and emissary to Neat United kingdom wrote to Wilson, "America has come to a parting of the means when she must determine whether she stands for civilized or uncivilized warfare. We can no longer remain neutral spectators." (Diana Preston, Lusitania: An Epic Tragedy ) The American public was not so rabid . A popular vocal written immediate ly after the sinking, "When the Lusitania went Down," past Charles McCarron and Nathaniel Vincent, mourns the passengers, but does not assign arraign, "Although they were warned, the warning they scorned, And now nosotros must cry in despair!" In fact, the song goes every bit far as to warn American travelers to sail just on American ships since "A Yankee tin get anywhere; Equally long as Old Glory is there."

German Americans were in a tough spot . They identified as Americans, but yet felt ties to the home of their ancestors and the source of many family traditions . Fearing a rush to war, German-American newspapers and magazines advoc ated neutrality. The Fatherland ; Fair Play for Germany and Austria-Hungary , published in New York past George Sylvester Viereck , alleged:

The German-Americans stand up where all good Americans stand. In instance a strange power were to attack the The states, justly or unjustly, they would rally to the defense of their country. If the United states of america were to attack a strange power for adept and sufficient reason, they would be ready to shed their claret for the country of their adoption. But they volition not let a small clique of Oyster Bay politicians and pink editors to jockey this country into an unjust war. (five. 2, no. 15)

F ocused on the artillery supposedly ferried by the Lusitania , the Fatherland blamed the British and American governments for putting civilians in harm's manner. "[T]he State Department should issue at once a formal notice admonishing American citizens to shun all ships flight the flag of a belligerent nation and all ships, irrespective of nationality , which carry beyond the sea the tools of destruc tion." (v. two, no. xv)

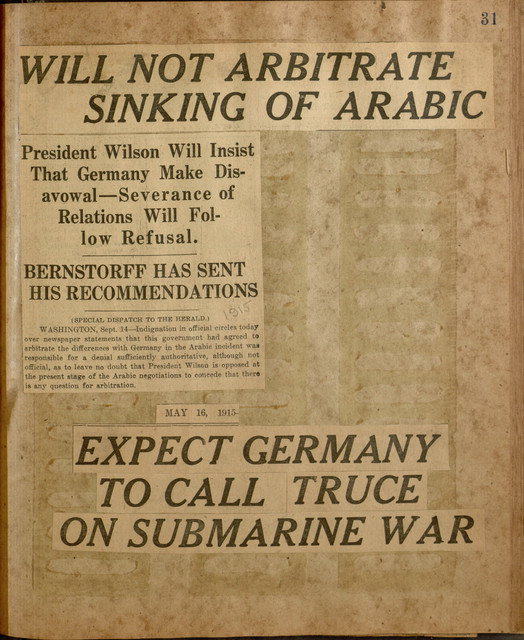

Later on much thought, President Woodrow Wilson, intent on preserving neutrality, had Secretary of Land William Jennings Bryan send a stern, but noncommittal, annotation castigating the German regime for its utilise of U-boats to assail merchant ships in "inevitable violation of many sacred principles of justice and humanity." The U.s. demanded that German y decry the actions of the U-xx and other submarines responsible for attacks on merchantmen, make reparations for the damages, and terminate the submarine war against merchant ships . The Imperial administration apologized for the attacks on American ships, only was unrepentant nigh the Lusitania . "The German Authorities believes that it acts in simply cocky-defense when it acts to protect the lives of its soldiers by destroying ammunition destined for the enemy … In taking [passengers] on lath … [Cunard] quite deliberately tried to use the lives of American citizens as protection for the ammunition carried." The adjacent American note was more vigorous, and caused the resignation of Secretary Bryan . He felt that , as a neutral country, the United states should exist protesting both the High german and the British actions that put Americans in harm's way. Unrestricted warfare only came to an end with th e August sinking of another passenger liner, the S.S. Arabic , and the deaths of 3 more Americans.

If the British hoped that the sinking would spur United states to enter the war, they were disappointed. T he US did not declare war on the Primal Powers for another two years. All the same the Lusitania became forever linked to American participation in the Great War. Conspiracy theorists posited that the Admiralty did not exercise more to protect the Lusitania non because the government wished to hibernate their intimate k nowledge of German movements, bu t because they were looking for a true cat al yst to propel the United States into war. Oft cited to bolster this theory is Winston Churchill's letter to the head of England's Lath of Trade, Wal ter Runciman , in which he declares his conventionalities that American shipping traffic had been reduced by the threat of High german submarines. (He did not consider that the British confiscation of all m oods it labeled every bit contraband mi ght take had an influence) It was "near of import," he declares, "to attract neutral shipping to our shores … the more than the better; and if some of information technology gets into trouble, better nevertheless." Fifty-fifty Male monarch George V, meeting with American emissary Edward M. Firm, wondered, "Suppose they should sink the Lusitania wi th American passengers aboard?" Whether a sacrificial lamb or not, the Lusitania did non get a twentieth century Maine. She was i of many ships, including several American flagged merchants, sunk during this kickoff period of German unrestricted submarine warfare. Although horrified at the enormous loss of life, the Americans were shortly reading other headlines equally the Lusitania slipped from the headlines to the back pages.

Propagandists on both sides used the sinking to rally support. In Germany, artist Karl Goetz designed and struck a medal to celebrate the achievement. Under the headline, "Geschäft Über Alles" or "Business Above All," passengers, including a man reading a newspaper with the warning, "U-Boat Danger," are lined up at the Cunard part to buy tickets from Expiry. The obverse title is, "Keine Bann Ware" or "No Contraband," and depicts a Lusitania loaded with munitions. Below the transport is written, Der Gross-Dampfer Lusitania Durch Ein Deutsches Tauchboot Versenkt 5 Mai 1915' or "The liner Lusitania sunk by a German submarine, v May 1915." The appointment the Lusitania went downwards was really May viith. British Propagandists seized on this error as proof that the German Navy was lying in wait for the rider transport and produced 300,000 copies for sale, accompanied by a flyer stating that "This medal has been struck in Germany with the object of keeping alive in German language Hearts the recollection of … deliberately destroying an unarmed passenger ship together with i,198 non-combatant men, women, and children." Cartoonist Winsor McCay made the sinking the subject of the first animated documentary. His twelve minute film condemned "the most violent cruelty that was ever perpetuated upon an unsuspecting and innocent people." The New York Times deputed Joyce Kilmer to write a poem for its mag department. Entitled "The White Ships and the Scarlet," Kilmer writes of the honorably sunk "white" wrecks on the sea floor, led by the Titanic greeting the Lusitania stained scarlet past a "loathly deed." Despite the propagandists' all-time efforts, the Usa did not rise upwardly to avenge the 128 Americans lost on the Lusitania, simply they did inexorably tie the ship to the eventual proclamation of war in 1917.

Propagandists on both sides used the sinking to rally support. In Germany, artist Karl Goetz designed and struck a medal to celebrate the achievement. Under the headline, "Geschäft Über Alles" or "Business Above All," passengers, including a man reading a newspaper with the warning, "U-Boat Danger," are lined up at the Cunard part to buy tickets from Expiry. The obverse title is, "Keine Bann Ware" or "No Contraband," and depicts a Lusitania loaded with munitions. Below the transport is written, Der Gross-Dampfer Lusitania Durch Ein Deutsches Tauchboot Versenkt 5 Mai 1915' or "The liner Lusitania sunk by a German submarine, v May 1915." The appointment the Lusitania went downwards was really May viith. British Propagandists seized on this error as proof that the German Navy was lying in wait for the rider transport and produced 300,000 copies for sale, accompanied by a flyer stating that "This medal has been struck in Germany with the object of keeping alive in German language Hearts the recollection of … deliberately destroying an unarmed passenger ship together with i,198 non-combatant men, women, and children." Cartoonist Winsor McCay made the sinking the subject of the first animated documentary. His twelve minute film condemned "the most violent cruelty that was ever perpetuated upon an unsuspecting and innocent people." The New York Times deputed Joyce Kilmer to write a poem for its mag department. Entitled "The White Ships and the Scarlet," Kilmer writes of the honorably sunk "white" wrecks on the sea floor, led by the Titanic greeting the Lusitania stained scarlet past a "loathly deed." Despite the propagandists' all-time efforts, the Usa did not rise upwardly to avenge the 128 Americans lost on the Lusitania, simply they did inexorably tie the ship to the eventual proclamation of war in 1917.

Was the liner a lure , dangled by the British, to bring the United States into the War t o Finish All Wars ? Could the meeting of the U-20 and the Lusitania have been avoided? The Admiralty , knowing that the U-20 had sunk iii ships in the days earlier meeting the Lusitania, could have warned the Captain Turner , sent the liner on the northern route by Ireland, or provided a naval escort. The subject remains controversial to this day, but the fact is that the oft told tale of the Lusitania's demise bringing the United States into the war, is not truthful. While this was something the British hoped for, and the Germans feared, America did not enter the war for another two years. Americans were horrified past the tragedy and sympathetic to the British, but the majority were not interested in ending the country'southward isolation. What makes this tragedy stand out, beyond the send'due south fame and the enormous human toll, is the place the ship occupies on the ill-defined line between innocent traveler and war conspirator.

[AED]

References:

Archer, William. The Pirate's Progress: A Short History of the U-Gunkhole. New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers, 1918.

Bailey, Thomas A. and Ryan, Paul B. The Lusitania Disaster: An Episode in Modern Warfare and Diplomacy. New York: The Free Press, 1975.

Balfour, A.J. The British Blockade. London: Darling & Son, Express, 1915.

Ballard, Robert D., and Spencer Dunmore. Exploring the Lusitania: Probing the Mysteries of the Sinking That Changed History. New York: Warner Books, 1995.

Brewer, Daniel Chauncey. Rights and Duties of Neutrals: A Discussion of Principles and Practices. New York: G.P. Putnam, 1916.

The Catholic Standard and Times, v 20, No. 27 [26 Sic], Saturday, May 15, 1915.

Chevalier, Jack. Postcard, To: B. Chiliad. Landstaff From: Jack Chevalier, June 9, 1909.

Cooper, John Milton. Walter Hines Folio: The Southerner As American, 1855-1918. Chapel Loma(NC): University of North Carolina Press, 1977.

Dewael-Grootenburg."Vijftien Meter Onder Zee." De Oorlogsspien. Amsterdam : Roman-Boekhandel, 1915.

Doyle, Arthur Conan. "Danger! Being the Log of Captain John Sirius." The Strand Magazine, July 1914, pp. 3-22.

Eastman, Max. Agreement Germany: The Only Way to End War, and Other Essays. New York: M. Kennerley, 1916.

The Gaelic American. New York [NY]: The Gaelic American Publishing Company.

Gibbs, Henry Railton. "Dos Corazones en un Submarino," Los Dramas de la Guerra no. 33.

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von. Great U.k. 1917 - WW1 Goethe Anti-German Propaganda Contumely Medal - Nach Paris. 1917.

Goetz, Karl. Lusitania Medal. 1915.

Henschel, Albert Edward. The "Lusitania" Instance: Was Bryan's Resignation Justified? New York: H.H. Masterson, 1915.

Hilfsverein Deutscher Frauen and Viereck, George Sylvester. Earth-War: An Exact Translation of Weltkreig, an Accurate Daily Record of the Present War. New York: Hilfsverein Deutscher Frauen, 1915.

Hoeling, A.A. and Hoeling, Mary. The Concluding Voyage of the Lusitania. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1956.

Hough, Richard. The Dandy War at Ocean, 1914-1918. New York: Oxford University Printing, 1983.

Hoyle, John Thomas. In Memoriam: Elbert and Alice Hubbard. East Aurora, N.Y.: Done into a volume and printed by the Roycrofters at their shop, 1915.

Hubbard, Elbert, and Felix Shay. The Fra: A Periodical of Affidavit. East Aurora, N.Y.: Roycrofters.

Hubbard, Elbert. Who Lifted the Hat Off of Hell? 1914.

Kilmer, Joyce and Robert Cortes Holliday. Joyce Kilmer. New York: George H. Doran and Company, 1914. v.one.

König, Paul. Voyage of the Frg, the Starting time Merchant Submarine. New York: Hearst's International Library Co., 1916.

Lauriat, Charles Emelius, and Elbert Hubbard. The Lusitania'due south Last Voyage: Being a Narrative of the Torpedoing and Sinking of the R.M.S. Lusitania By a German Submarine Off the Irish Coast May 7, 1915. Special Edition Limited to 250 copies. Boston ; New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1915.

Layton, J. Kent. Lusitania; An Illustrated Biography. Stroud: Amberley Publishing, 2010.

Lusitania (Steamship), and Cunard Line. Lusitania Menu and Ticket Collection.

Lusitania Supplementary Cargo Manifest, Crossing 202, New York to Liverpool, filed five May 1915, courtesy Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Annal/RMSLusitania.info.

McCarron, Charles R. and Nat. Vincent. When the Lusitania Went Downward. New York (231-235 West. 40th St., New York): L. Feist, 1915. Listen to the 1915 recording by Herbert Stuart

Milner, Alfred, Viscount. Cotton Contraband. Darling & Son, Express, 1915.

Molony, Senan. Lusitania: An Irish Tragedy. Douglas Village, Cork: Mercier, 2004.

Muir, Ramsay. Mare Liberum; The Liberty of the Seas. New York: Hodder & Stoughton, 1917.

Paper Scrapbook, World State of war I, 1915-1917.. New York: Daniel Slote & Company.

O'Leary, Jeremiah., and L. Helmholtz (Illustrator) Junker. The Fable of John Balderdash and Uncle Sam New York: American Truth Society, 1900.

Pansing, Fred. The Cunard Line Steamships. Cunard Line, and American Lithographic Co. [New York].

Preston, Diana. Lusitania: An Epic Tragedy. New York: Walker & Co., 2002.

Roosevelt, Theodore. Murder on the Loftier Seas. New York: The Metropolitan Magazine, May xi, 1915.

Sauder, Eric. The Unseen Lusitania; The Ship in Rare Illustrations. Stroud: The History Printing, 2015.

Simpson, Colin. The Lusitania. Boston: Petty, Brown, 1972.

Star & Herald, Sun, May 9, 1915. Panama City [Panama]: Star and Herald Co, 1915.

The Cunard Turbine-driven Quadruple-screw Atlantic Liner "Lusitania": Synthetic and Engineered By Messrs. John Brown and Co., Ltd., Sheffield and Clydebank. Wellingborough: Stephens, 1986.

"The United States and the state of war; President Wilson'south notes on the Lusitania and Deutschland's respond; diplomatic correspondence between Germany, England and the United States on events preceding the sinking of the Lusitania, with decrees and incidents affecting American lives, property, and rights in the war zone. Brooklyn[NY]: The Brooklyn Daily Hawkeye, 1915.

Viereck, George Sylvester and Frederick F. Schrader. The Fatherland. New York: International Monthly Inc.

Vital Issue. New York : F. J. L. Dorl, 1915.

Wise, Bernhard R. The Freedom of the Seas. London: Darling & Son, Express, 1915.

Related Articles:

To Strike For Freedom: The 1916 Easter Rise and the United States

The United states of america played a critical role in the planning and aftermath of the 1916 Easter Rising. This article examines the ways in which the Irish American customs supported the Irish gaelic nationalists involved in the 1916 Rising with material, logistical, and moral support. Although the Easter Rising did non immediately upshot in the establishment of an Irish Commonwealth, the assist of the Irish American community helped the Irish nationalists constitute an independent nation in the years following the Rising.

The Complex Case of the RMS Lusitania

Equally May arrived in 1915, soldiers were mired in trenches across France and Kingdom of belgium, toxicant gas had been deployed against troops of both sides, and Frg had begun rationing food owing to a British naval blockade. The Royal Navy stopped all ships suspected of carrying cargo to the Central Powers and confiscated the materiel. In retaliation, Germany declared the waters surrounding the British Isles a war zone and sent U-boats to patrol the area. In this tense atmosphere, the great Cunard liner, RMS Lusitania, began her 202nd transatlantic crossing carrying 1,265 passengers, 694 crew, $735,579 in cargo (1915 value), and three German speaking stowaways.

Journalism and the Great State of war

When the Slap-up War inverse the course of the 20th century, it likewise greatly impacted the world of communication.

Source: https://exhibits.library.villanova.edu/wwi-online/articles/complex-case-rms-lusitania

0 Response to "What Law Was Passed to Prevent Lusitania Type Incident Again"

Post a Comment